Welcome back! Let’s get to it.

Phantoms in the Eyes

One chapter of my forthcoming book focuses on prison design and whether it’s truly possible to create “humane” prisons. As part of my research into the psychological effects of incarceration, I spent a lot of time reading about the absolutely devastating consequences of solitary confinement. Solitary is, as one of my sources put it, “just toxic to human beings.” People who are sent to solitary often deteriorate rapidly, developing symptoms that range from anxiety and confusion to headaches and heart palpitations. A significant proportion — roughly 40 percent, according to one study — report perceptual distortions and hallucinations.

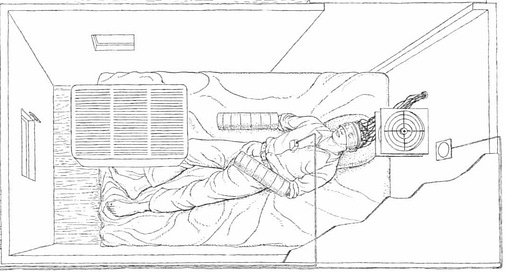

Researchers now mostly agree that solitary does much of its damage through social isolation, but sensory deprivation may play a role, too. Consider a classic study from the 1950s, in which scientists at McGill University asked student volunteers to spend days lying on a cot in a cubicle, wearing frosted visors over their eyes and u-shaped pillows over their ears. Here’s a sketch of the set-up, from a 1957 account of the study:

This sensory deprivation caused all sorts of problems, including irritability and restlessness. The students also began to hallucinate, and what I found particularly interesting is how the visual hallucinations evolved over time. Here's what the researchers reported:

Our subjects' hallucinations began with simple forms. They might start to 'see' dots of light, lines or simple geometrical patterns. Then the visions became more complex, with abstract patterns repeated like a design on wallpaper, or recognizable figures, such as rows of little yellow men with black caps on and their mouths open. Finally there were integrated scenes: e.g., a procession of squirrels with sacks over their shoulders marching 'purposefully' across the visual field, prehistoric animals walking about in a jungle, processions of eyeglasses marching down a street.

It’s now clear that hallucinations are a common side effect of sensory deprivation, even short-term deprivation. When the flood of sensory input dries up, the brain seems to compensate by “filling in” the gaps and trying to make sense of whatever sensations remain. (Even in the most restricted environments, in which seemingly all external stimuli are blocked, the body still generates its own internal sensations.)

In any case, this has been on my mind lately because I recently received the following email from my dad, who had just had eye surgery:

After my surgery they put a dark patch over my left eye. It first, everything was dark on that side, as you'd expect. Then I started to “see” random white lights on the left. That can be a danger signal for a detaching retina. Then, over hours, the lights became recognizable images, gradually brighter and sharper, and in color. I guessed that it was my visual cortex replacing the “missing” eye with a phantom one. My doctor confirmed that this AM.

But as the phantom image gets stronger, it is now starting to mix with the real image on the right, and that's making things pretty confusing. Sometimes the phantom image is the thing I'm looking at that exact moment, but particularly bright or colorful images can persist for a minute or two. I assume this will go away when the patch comes off Thurs.

Cheers,

The Man Who Mistook His left Eye for His Right Eye

The visions did indeed go away when the patch came off and never seemed to progress so far as “processions of eyeglasses marching down a street.”

Indoor Ephemera

I’d like to use this newsletter, in part, to feature other interesting stories that highlight the power of the indoor environment. Here are a few I’ve come across recently:

How Google Got Its Employees to Eat Their Vegetables by Jane Black for OneZero. Key quote: “‘There is no prescriptive: Thou shalt eat carrots.’ It’s just that the environment has been subtly engineered to make carrots more appealing.” (Note: I have a lot more on these design strategies in my book, for which I visited an elementary school in Virginia that’s putting many of these principles into practice.)

Some cities are finally making a serious investment in climate change resilience, creating more “water-absorbing green space, storm-surge-proof seawalls, and elevated buildings,” Adam Rogers writes in Wired. But these “adaptations” are also having another, more insidious effect, he explains: “In real estate lingo, ‘adaptations’ are also ‘amenities,’ and the pursuit of those amenities ends up displacing poor people and people of color. The phenomenon has a name: green gentrification.”

Indoor environments can provide a physical infrastructure that allows pathogens to spread. Exhibit A: The corona-virus-covered Diamond Princess cruise ship. “A ship’s ventilation system, which relies on recirculated air filtered by medium-strength air filters, is an efficient way of spreading virus particles from room to room,” Dan Vergano writes for BuzzFeed News.

Finally, if you were looking for a sign that perhaps the open office trend, which employees almost universally hate, has gone too far, look no farther than this administrator, who wrote in to Ask A Manager about not having enough privacy to fire someone:

I’m an HR administrator at a company with about 150 people across a few offices. I’m the only on-site HR person at my location, which has about 25 employees. Our office is entirely open plan, with the exception of a few fish-bowl style, glass-walled conference rooms. There aren’t even dividers between desks, just one big room, so everyone can see everything that’s happening.

Unfortunately, we have had to terminate a few people over the course of my time here, typically for not meeting performance goals (as opposed to gross misconduct or misbehavior). Typically, the terminated employee gets the news in a conference room and is escorted out by their manager, which has had varying levels of success. There was one mishap where the manager allowed the terminated employee to return to his desk to collect some things, which ended in an awkward conversation with some of the folks at the desks surrounding his.

Obviously, people may immediately need to collect items at their desks (coats, wallets, etc.), but that can be mitigated by someone else taking those items. My question is then, what is the best way to handle employee termination in an open office, where it can become obvious what’s happening?

Bonus Interspecies Animal Content

As promised!

Till next time!

Emily

•

The Great Indoors will be out in June! But you can pre-order it now at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Powells, or your local independent bookstore.

You can read more of my work at my website and follow me on Twitter, Instagram, and Goodreads. (You can follow me on Facebook, too, I suppose, but I rarely post there.)